The English Concert embarks on an ambitious project to film and release Handel’s complete works online

On a sunny afternoon in south London, in the faded splendour of Battersea Arts Centre’s Grand Hall, two prostitutes are locked in a ferocious argument. Egging them on are Harry Bicket and the 20-odd players of The English Concert, while the orchestra’s co-principal viola ensures that the whole thing is captured on camera.

Handel’s Solomon, with its two warring harlots and wise king, is one of the first works in the ensemble’s sights for a new project so grand and so ambitious that the Queen of Sheba herself might blanch at the prospect. Handel for All will see the composer’s entire catalogue – all 42 operas (in concert performances), 29 oratorios, well over 100 cantatas, concertos, and chamber works of all kinds – filmed by the orchestra and released online, where it will exist in perpetuity as a library and archive: freely available to everyone.

It would be a vast undertaking at the best of times. At a moment of economic crisis, with arts funding and audience numbers in the UK more precarious than ever before, it’s an extraordinary gesture – a defiant vote of confidence not just in these musicians, but in the future of classical music itself, says principal cellist Joseph Crouch: ‘That sense of optimism – that there were enough people out there who were so positive, both about what we do as a group and about the industry itself – was just such a tonic.’

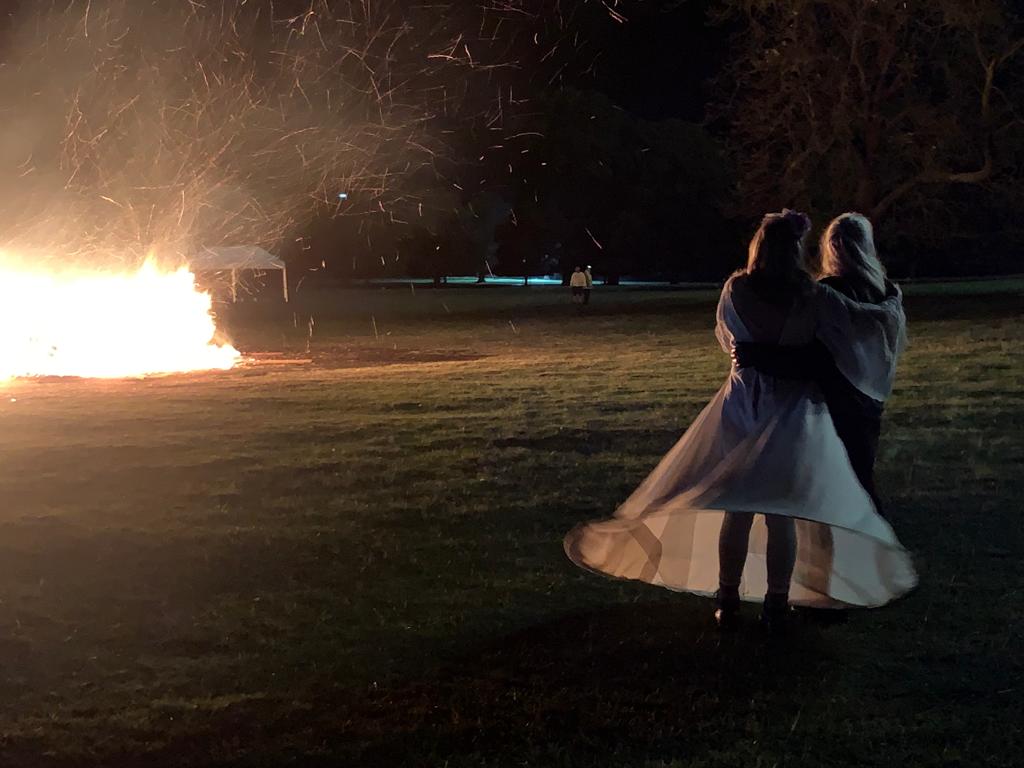

The English Concert directed by Harry Bicket in Serse at St Martin-in-the-Fields Church, London, May 2022, with Paula Murrihy as Arsamene (left) and Emily D’Angelo as Serse (photography: Paul Marc Mitchell)

It’s a project that was conceived at arguably the lowest moment in cultural memory, at the height of the pandemic in 2020. ‘An orchestra is not like an actor who can “rest” for years and still be an actor,’ Artistic Director Harry Bicket says. ‘An orchestra that’s not working, not playing together, not making music, not performing for live audiences, really stops being an orchestra.’ His response? It was to double down. ‘Whereas many organisations contracted during Covid, we thought: “If this is the end of the orchestra as we know it, what should we do?”

‘Of necessity during lockdown we began thinking about the way people were consuming music, and how that was changing. We did a lot of streaming ourselves and invested a lot in equipment, and that was when the idea first emerged to create some kind of digital library or archive. That soon became: “Let’s do all of Handel’s works.” So now we’re committed to finding these pieces and performing them all.’

‘People are doing things every day in performances that just beggar belief’

Joseph Crouch, principal cello

All of them – really? Bicket hasn’t done the maths on the project (‘I probably should have!’), but there’s an initial five-year plan, with every chance of extending beyond. ‘It’s fascinating for me,’ he says, ‘because I thought I had pretty much done most of it, but apparently not! One of the advantages about having committed to doing it all is that you’re not caught up in debating which pieces you should do: it’s a question of logistics, not aesthetics – though there is the question of whether we do every single version of particular works. We want to cover all the material, but without being too academic about it. It’s a bit insane, but being ambitious is no bad thing – it’s much better than just scrabbling around for the next concert.’

Opera lovers who have followed The English Concert’s sold-out series at Carnegie Hall, New York, and London’s Barbican – the concerts that launched the group’s recent success with Handel – can be reassured that lots of the big-name stage works will be in the early batches: Orlando, Alcina, Giulio Cesare in Egitto. But there will also be plenty of rarities. ‘I’ve always wanted to do Deidamia – Handel’s last opera,’ Bicket admits. ‘And also a piece like Ottone, re di Germania, which I think has some of the most beautiful music Handel ever wrote, but which is completely impossible to stage. I defy anyone to make it work! Doing it in concert is brilliant as you don’t have to suspend disbelief in the same way.’ Jephtha (‘I haven’t done it for years’), Alexander’s Feast and Belshazzar (‘such a strong piece, and I’ve never done it’) are also firmly in his sights.

Bicket will direct all he can – ‘I’m not greedy, though, and I am aware that I can’t do it all’ – but will hand over the reins for particular performances, such as last summer’s Saul from the Edinburgh International Festival, directed by John Butt. Principal Guest Conductor Kristian Bezuidenhout will also be stepping forward regularly. Chamber works like the trio sonatas Bicket is happy to leave to his musicians – a rare opportunity, Crouch says, and one they’ve relished. ‘It has been such a joy to play with different combinations of people,’ he says. ‘There is a real familiarity and trust between the players in The English Concert that is really hard to achieve in a freelance context, and I would hope that in these video recordings you’ll see that camaraderie, the delight we all take in each other’s work. There are people doing things every day in performances that just beggar belief, as far as I’m concerned.’

Bicket and The English Concert performing at the Barbican, London, in March this year – recreating Handel’s 1749 benefit concert in aid of London’s Foundling Hospital (photography: Mark Allan)

The choice to make Handel for All a video rather than an audio project is an interesting one for a group with a stellar recording catalogue behind them – particularly at what feels like a watershed moment for the recording industry. The decision, Bicket explains, was twofold, with advantages for both the audience and the musicians themselves. ‘It’s a slightly sacrilegious thing to say, particularly in Gramophone, but I don’t love the process of recording. For me, being forced (or that’s how it seems) into saying “this is the way I think this piece should go” is not a very natural way of making music. And then, of course, you have producers focusing on tiny details of intonation or articulation, which is important, but in a concert that’s not my priority, nor the orchestra’s, particularly. If it’s all immaculate then that’s great, but if it’s not, that’s fine too. I’m not looking at these performances as a permanent or iconic statement. They represent a snapshot, a moment in time.’

Recordings, Bicket argues, may have given us greater virtuosity and precision, but they’ve also taken us further away from original principles and context. ‘We know from Handel’s own writings and from commentators like Charles Burney that what was valued above all in performance was a kind of sincerity of utterance,’ he says. ‘Poor Mrs Cibber, famously, did not have a particularly beautiful voice, but her “pathos” and “dignity” were so highly praised. That’s something I think we’ve lost; we’ve forgotten what actually moves people, what really makes a performance.’

‘On CD there’s an expectation of perfection,’ Crouch adds. ‘On video it’s not about that, it’s about intensity, a directness of communication. We have to be compelling in everything we do, to try to recreate the experience of hearing this music live. I think that has already helped me to refocus on how things come across, how I communicate them.’

The project doesn’t just offer their regular audience a different way of engaging, it also invites in a whole new crowd

Just as contexts and conventions of performance have evolved, so have audiences themselves. A video-based project that’s available on demand, from anywhere, that takes you right into the musical action in close-up, even delivering the highlights in convenient pre-edited chunks, doesn’t just offer the ensemble’s regular audience a different way of engaging, it also invites in a whole new crowd: geographically, demographically and economically.

Crouch compares it to cricket. ‘People saw the short form game as possibly being the death of Test match cricket. Now it seems as though the reverse is true: the intensity of short-form cricket has been imported back into the longer game, and there’s a real buzz around it.’ He points me towards one of The English Concert’s most successful videos: a 20-second clip of a double-bass player performing furious semiquaver scales. Hundreds of thousands of people watched it within just a few hours on social media. If even a handful then choose to follow that musician across the archive and discover a full-length concert or opera, that’s a win.

‘We get over a million hits a year on Spotify, and 10,000 a day on Apple Music,’ Bicket says. ‘We never see anything like that number at our concerts; I suspect they are two almost completely separate audiences, and that’s OK. Video offers people a little window you don’t get with a CD – a totally different kind of musical experience. Filming allows us, as a baroque orchestra, to show people spaces they might not otherwise see and to play music that’s appropriate to or even associated with that particular building.’

Podcast – Handel: a portrait

Today the group are in Battersea, but they’ve already filmed performances at southeast London’s Eltham Palace, at Handel’s own church in Hanover Square and in the Great Hall at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, watched over by a huge portrait of Henry VIII. It’s just the start, Bicket hopes. ‘You don’t have to go far to find all sorts of venues associated with Handel across the UK, whether it’s Boughton House in Northamptonshire, Malmesbury in Wiltshire … I’d love to do Handel’s anthems from the chapel royal. And what about a sort of Cook’s tour of organs for the concertos? I have this wild fantasy that we could do them almost anywhere in the world.’

But while setting is important, the music, Bicket stresses, remains the focus. ‘I get driven nuts by endless panning shots of vaulted ceilings while people are playing – it’s like someone’s attention is wandering, which may be realistic, but doesn’t necessarily make for a good experience.’

Viewers can expect a more classic, proscenium-style approach from The English Concert’s films – a chance to see the ‘physical action and exertion’ of performance without too much hyperactive or interventionist camerawork. ‘We do old music,’ says Bicket, ‘music that is hundreds of years old on historical instruments. We can’t sex that up beyond a certain degree, nor should we. I think people get that; even if they’re not familiar with the music, they can see that it’s being done with a level of commitment and skill which you can just sense.’

‘Singing is the most personal art form – it’s your vocal cords, it’s you. But it’s also your soul, your heart. I like singers who reveal something of themselves’

Harry Bicket, director

After an initial year spent building up the digital library, year two (fundraising allowing – to be able to continue, the project will require £350,000 each year on top of the group’s usual budget) will introduce a new focus on educational strands. Bicket explains, ‘There will be interviews with players and singers, all sorts of people involved in the project. When we do concerts it’s always interesting to see the degree to which people are fascinated by period instruments. We call it the “petting zoo” – people come down to the front of the stage to see them close-up. And then there are the scores; lots of them are really just sketches. We see a rhythm and just naturally swing it. It’s a whole unspoken musical rhetoric that audiences aren’t necessarily aware of. You look at Handel’s music on paper and it doesn’t give up all its secrets – not in the way that a Stravinsky score does.’

Anyone who has ever dreamt of joining The English Concert will also get the chance, thanks to a ‘music minus one’ series that allows viewers to turn performer, of playing along with prerecorded orchestral parts – something Bicket himself remembers doing as a teenager with Beethoven piano concertos. ‘Handel coincided with the rise in publishing and a new group of middle-class amateurs,’ he explains, ‘so much of his music is written in such a way that it could be played at home – all those trio sonatas with their interchangeable violin, oboe and flute parts, for instance. Some of them are technically quite hard, but you can still have fun playing them, and that’s what it’s about.’

Education is baked into The English Concert’s structure. A fellowship programme with the Juilliard School in New York sees the best student instrumentalists come over to play with the orchestra, and some have since gone on to become regular members, while Bicket’s role as Music Director at Santa Fe Opera with its cohort of more than 40 Apprentice Singers ensures a constantly refreshing flow of young soloists. But school-age children are a different, and more difficult, matter. With music education slipping from the curriculum, increasingly palmed off on ensembles themselves, will future students even have the capacity to take advantage of the resources a project like Handel for All offers?

‘I don’t know,’ Bicket admits. ‘It’s a conversation we’re having the whole time. The English Concert has a turnover of £1 million a year, but we only employ three people in the office – it’s that lean. If we want to put on an education project with a hundred kids, who is going to do that? Where can we find the resources? But we believe passionately in that kind of work and do what we can, so if we’ve fundraised to film a performance, then we’ll try to bring in a whole load of children for the final run. That way, I’m hoping that we can at least start to draw them in, because – in my experience – kids don’t come with any cultural baggage; they are totally open.’

The roster of soloists joining The English Concert for the project is already a starry one. Mary Bevan, Lucy Crowe, Emily D’Angelo, Iestyn Davies, Stuart Jackson: beautiful voices, all, but (crucially) more than that. ‘In many ways, singing is the most personal art form,’ says Bicket, ‘because it’s your vocal cords, it’s you. But it’s not just your vocal cords; it’s also your soul, your heart. I like singers who reveal something of themselves.

‘I did a lot of work with Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. There was nothing she wouldn’t dare to do in terms of the depth of emotion she drew on. Music-making wasn’t an escape for her, it was a kind of therapy, a working-through. I think for an audience to have someone who can do that is pretty powerful. There are lots of reasons why someone watches a performance, but I think part of it is because the musician speaks things that can’t otherwise be spoken.’

Handel has been at the centre of Bicket’s own performing life for an entire career, so the choice of composer for the project was never in question. ‘For me, it comes down to the humanity of the way he writes. People always get hung up on the crazy opera plots, but that’s not what he’s writing about. He’s writing about who these people really are, and that’s what touches listeners. And he does it with a directness of emotion and a simplicity, with very few notes. Wasn’t it Beethoven who said: “If you want to make the biggest gesture with the smallest number of notes, look at Handel”? And OK, so he was a little bit German, but he’s just an iconic English composer. If you go to Salzburg you can’t avoid Mozart, in Bonn it’s all about Beethoven. You come to London and, well … We just don’t celebrate Handel in the way any other country would. I think this is an important opportunity for The English Concert finally to do that for this English composer.’

Visit englishconcert.co.uk, and sign up to be notified of video releases

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today