The ocean’s engine, and the science of reading: Books in brief

Blue Machine

Helen Czerski Torva (2023)

Few scientific subjects are so vast, and yet oceans “often seem invisible”, remarks physicist and broadcaster Helen Czerski; the workings of the seas got no mention in her physics training. She now studies the bubbles created by breaking waves and their influence on weather and climate. Her profound, sparkling global ocean voyage mingles history and culture, natural history, geography, animals and people, to understand the “blue machine”: the ocean engine powered by sunlight that shunts energy from Equator to poles.

The Science of Reading

Adrian Johns Univ. Chicago Press (2023)

Starting in the 1880s with US psychologist James Cattell, the experimental study of reading dealt in extremes, notes information historian Adrian Johns in his intriguing analysis. Researchers devised mechanical ways to measure quantities that were nearly imperceptible, such as pauses in motion as an eye scans prose. Yet they were certain that the work had vast consequences — that “civilization itself depended on those measurements”. Today, scanners can measure brain activity, but the reading process remains mostly imponderable.

Meetings with Moths

Katty Baird Fourth Estate (2023)

Ecologist Katty Baird’s fly-specialist friend grumbles that butterflies should be renamed ‘butter-moths’. Butterflies and moths belong to one order, and are not always easy to tell apart. However, most butterflies rest with wings shut, whereas resting moths display theirs. The garden tiger moth (Arctia caja), for example, has “forewings a mosaic of darkest brown and white which conceal shocking scarlet underwings spotted with denim blue”. Happily for roaming moth-inspector Baird, her household has been spared the ravages of clothes moths.

A History of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3

John Romer Allen Lane (2023)

This deeply informed history by Egyptologist John Romer focuses on the New Kingdom, 1550–1185 bc, including rulers Nefertiti, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II: crucial figures in popular perception. Calling it the “most fantasized period in all of ancient history”, Romer criticizes much scholarship on the era for being “firmly stuck” in the nineteenth-century European vision of ancient Egypt, launched by Jean-François Champollion in the 1820s. Romer avoids this pitfall, but ironically misdates Champollion’s pivotal visit to Egypt.

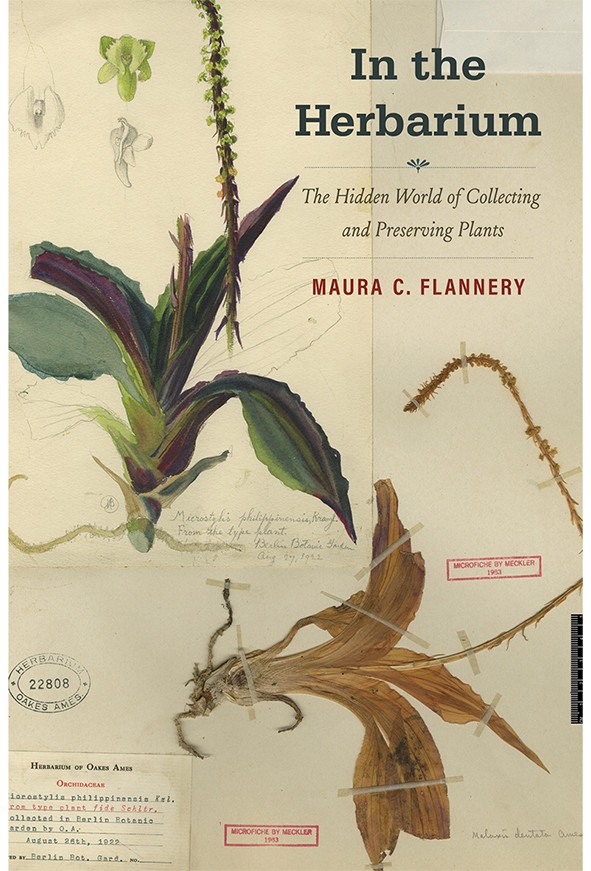

In the Herbarium

Maura C. Flannery Yale Univ. Press (2023)

London’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew are open to all. Not so Kew’s Herbarium, a collection of more than seven million plant specimens reserved for academic visitors. Access to most herbaria is restricted: biologist Maura Flannery knew “almost nothing” about them until 2010, when a US curator took her behind the scenes at one and she fell in love with them. Her history dramatizes this revelation, discussing global collections and collectors using fine period drawings, regrettably not in colour.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ae/f9/aef98f1b-7214-4eb2-be75-fa86735d08e5/dragonfly-and-kingfisher-stainless-steel-jason-heppenstall.jpeg)